Summary of Findings

- Building an online account that stands out from the crowd

- Outsourcing work

- Off-platform support

- Making the side hustle your full-time business

A side hustle is a money-earner employed in addition to a primary business or job. Side hustles come in all shapes and sizes, and are prevalent in some countries such as Kenya particularly among young men and women. As Muthoni Mwaura’s Kenyan study found “the notion of side hustling is particularly important for understanding youth livelihoods in contemporary contexts.”

It is hard to find a Kenyan who doesn’t have some sort of venture or job bubbling away on the side to supplement their main income. As Wambui succinctly put it:

“Everything here is just hustling, hustling, hustling.”

There are many offline examples of side hustles, such as those described by two of our interviewees, Rehema and Robert, below:

“Like for me I’m a hustler, when we don’t have these jobs, I try some other things….Like me at where I stay I’ll cook chapatis and sell 15 bob each.” —Rehema, Caterer

“It’s a farm…That one is my side hustle.” —Robert, E-Commerce merchant

But in this piece, we focus on digital side hustles which leverage platforms.

This section, one of two detailing “additional observations”, shares insights from our 27 interviews around how micro-entrepreneurs in Kenya are building their digital side hustles through online work platforms.

Defining the digital side hustle

In our research, the majority of digital side hustles were fulfilled through online work platforms. These platforms enable the sale and purchase of online task-based services, such as microwork and online freelancing. Among the microenterprises we spoke to who do online work, most of their work consisted of freelance writing, such as product reviews and academic writing. The sites they use included Upwork, Freelancer, Uvocorp, iWriter, and StudyBay. Most of our respondents also did online survey work, the channel through which we recruited the majority of our panel.

Small sample, fascinating findings

Our research in Kenya reinforces other work suggesting that a number of “traditional” Kenyan micro-entrepreneurs have taken to platforms to support their side hustles with remarkable aplomb. Among the 27 micro-entrepreneurs we met, 11 had side hustles, four of which were “digital”. This is in addition to two micro-entrepreneurs who do online digital work as their primary business. Read on for details about each of these six entrepreneurs:

Working with online work platforms as a side hustle:

- Otieno, a shoe merchant who does academic work on the side at night, averages 5-6 hours of online work a week, which he starts doing when he gets home at around 8:30 pm.

- Kamau, a pastor with a real estate business, completes roughly 15 surveys a month.

- Dorcas, a baker, makes 40% of her earnings through online work such as iWriter and Upwork.

- Daniel, who runs a small duka (convenience store) writes articles and does product reviews online in the evening through iWriter and Upwork.

Working with online work platforms as a primary business:

- Over the past two years Mary, an experienced online academic writer, has hired a staff of four to help support her online writing business.

- Kipchoge, an academic writer and Jumia representative, has completed 178 assignments on StudyBay over the last two years, which he considered a small number. Along with his girlfriend, they have five “freelancers” to whom they outsource work.

While we appreciate our sample size is small, we believe the insights we gathered from these six microentrepreneurs present an intriguing opportunity for further study and investigation. In our introductory Platform Practices Section we discuss how technologies are adapted to fit the needs of the user and ensure they get the most out of what these technologies offer. Online work platforms are no different. Both those who thrive and struggle across these platforms develop ways of improving their platform experience. In this section we will look at how a small selection of Kenyan micro-entrepreneurs behave across these online work platforms and how they bend rules to maximize these online work opportunities.

1. Building an online account that stands out from the crowd

Given the popularity of digital side hustles, competition is stiff and the oversupply of labor phenomenal. Research by the Oxford Internet Institute has quantified the incredible oversupply of labor among Kenyans working across one of the leading online work platforms. Their data from 2016 shows that, across one specific platform, only 6.9% of Kenyan account holders billed at least one hour of work or earned at least $1.

Despite being the most successful freelance writer we spoke to, Mary shared her experience of the oversupply of labor and undersupply of jobs:

“In the five clients that you talk to, one of them gives you a job…but initially you could even go for a whole week…you talk to hundreds and hundreds of clients…”

This competition, and ensuing race to the bottom when it comes to fees and wages, was evident in our user research. Kipchoge, another successful online freelance writer spoke of his experience with being outbid across online work platforms:

“There are writers who under-bid others because they already understand the instructions. For example, if an order is supposed to be paid USD$50 and this writer she has understood the order, the writer will under-bid me from my bid of $50 and place a bid for $40 or $35.”

Daniel also emphasized the extent to which fees are undercut on iWriter:

“For a 500-page doc, you are paid $3-5.”

Faced with this stiff competition, micro-entrepreneurs do what they can to stand out from the crowd. Below we highlight a number of strategies that they employ:

Designing an Online Profile

While we only have snippets of information on each of these subcategories, these observations were consistent among the six micro-entrepreneurs we interviewed who use online work platforms. These insights show the lengths to which micro-entrepreneurs will go to promote their online work profiles across heavily saturated platforms. Kipchoge, a seasoned user of StudyBay—an academic writing workspace—uses the picture of a white man as his profile picture (see image below). When we asked why he chose this picture, he said:

“Because the clients we are dealing with are usually from the West.”

Setting a “Home” Location

Along a similar vein, Njeru uses a VPN (avirtual private network) to trick his iWriter clients into thinking that he is located outside of Africa. He told us:

“If you want to write for such a site, you will get a virtual private network…If you are in Australia you get more jobs than in Kenya.”

Building up Ratings and Reviews

As discussed in detail in the Credibility Section, ratings rule the game across these platforms. The more traditional mode of building up ratings and reviews is to complete more jobs; to do so many digital side hustlers work late into (or even through) the night. However, some bypass this conventional approach in a bid to stand out from the crowd. Mary and Kipchoge who do online freelance writing as their main business “employ” freelancers to whom they outsource additional work. This inevitably increases the speed at which they can complete jobs and in turn build up their ratings. This is discussed in more detail in the following “Outsourcing Work” section.

While credibility is intended to be built on experience and quality of work, some entrepreneurs have learned how to hack the rating system. For example Njeru told us that some online micro-entrepreneurs in Kenya “review themselves” by logging into a platform as a client, posting a job, accepting and completing the job from their freelancer profile, and issuing their own review of their work!

“Kenyans are very crafty, creative and bright,” he told us.

Buying Second-Hand Accounts

We also found evidence of people selling and buying accounts for online work platforms. A number of micro-entrepreneurs told us about accounts being sold through Facebook groups, such as the image below captured from one of these groups. These pre-made profiles are designed to help users who either struggle to open their own accounts or want to buy highly rated and skill tested accounts to access higher paid jobs. For the account seller it’s a money earner in itself, creating a business by selling access to accounts on online work platforms. All they need to do is open an account, pass some skills tests, complete a couple of assignments, and then share the log-in credentials and related account details with the new account owner. Njeru explained what you get if you buy one of these accounts:

“Everything will be done for you, inputting profile information including email address and linking it to Paypal.”

Otieno, a shoe merchant and part-time online freelance writer, didn’t hesitate to tell us about the Upwork account he purchased.

“I bought an (Upwork) account from somebody…A friend of mine sold it to me.”

Various factors influenced his decision to buy an account, stemming from technology and literacy constraints in opening his own account, to challenges in passing Upwork skills tests, and lack of reviews and ratings to help him win his first assignments.

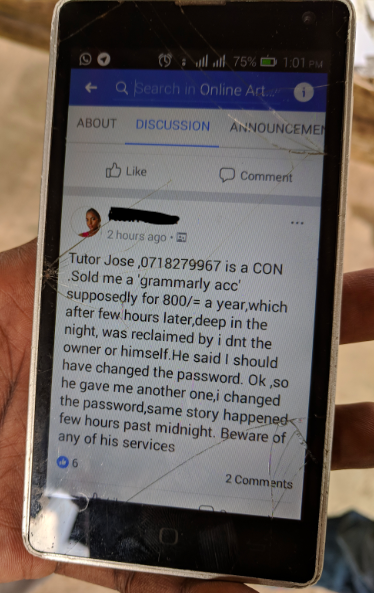

There are inevitable risks involved in the somewhat unethical purchase of pre-made accounts which are often (in the case of Upwork, Freelancer, and Uvocorp) linked to freelancers’ skill-level through various tests. The image below of a message sent across one of these Facebook groups, demonstrates the risks of purchasing a second-hand account.

Interestingly, one of the Facebook groups dedicated to this type of online work, warns group members against selling accounts (see image below):

2. Outsourcing work

According to our research the practice of outsourcing work acquired through online writing platforms is common for a number of reasons. Firstly, it helps those who can’t access their own online work – usually due to barriers to opening their own accounts or inability to win work due to intense competition – find outsourced work off the platform. Secondly, it enables those that have their own accounts, but wish to grow their online work business, to complete more jobs and generate more income. Thirdly, it assists those who purchase a secondhand account—and, in doing so, take on the account holder’s platform identity and experience—to complete assignments that the new user is unable to do based on their own knowledge and experience.

This process of reintermediation, in which successful online entrepreneurs become intermediaries themselves, has been found in other markets. Graham, Hjorth, and Lehdonvirta found evidence of successful online entrepreneurs in the Philippines and Kuala Lumpur purposefully “taking on more work that a single person can handle, and hiring other workers on the platform to carry out the work for them.”

In our own Kenyan research, Mary, who employs four people to support her online writing, explained:

“I realized working on my own, I don’t make much and I can actually pay someone to do it for me at a lower price. I got some people that I trained, now I just get to delegate them together on those jobs.”

While outsourcing work isn’t endorsed by platforms, it is a common practice. As Mary told us:

“the sites that we are using, they don’t know that we delegate to staff…they think that you’re working on your own…I am not sure whether it is okay if those websites learned that we do this.”

Account owners usually find extra staff through friends, family, or Facebook groups. Of the two Facebook groups we saw dedicated to online writing, one had over 100,000 members and the other over 55,000 members. From a quick review of one of these groups, we saw the proliferation of outsourced work in action. The image below is a screenshot from one of these Facebook groups through which a member is trying to recruit outsourced writers.

Why do online micro-entrepreneurs outsource work?

Similar to Mary, Kipchoge and his girlfriend both have StudyBay accounts and outsource work to a number of regular freelancers, or what he calls “colleagues”. This helps him fulfil jobs that require a specific skill set.

“With academic writing or with writing in general, you actually need someone who is special in something…someone who has special business related papers, accounting related papers, IT related papers… So, for example, if the order is for accounting, I already have my accounting guy. I just download the instructions, send to him and then once he has told me it’s okay…I’m able to place my bid now.”

While Mary also has a number of regular freelancers she works with, she also uses Facebook groups to find qualified people to complete specific jobs:

“Sometimes you’ll get a task that you don’t understand so you come to this (Facebook) group, and you post.”

Outsourcing work helps online work account holders grow their business. Online entrepreneurs need to complete more jobs and build up their reviews in order to stand out from the heavily saturated crowd of online freelancers. Outsourcing work helps them do this. Outsourcing work to multiple “colleagues”, enables entrepreneurs to work on multiple jobs at the same time and, in turn, rapidly build up their profiles and ratings. This is key to winning jobs across these platforms.

Who are they outsourcing this work to?

Not only does outsourcing work benefit account owners, it also benefits those who are either locked out from opening their own accounts or simply struggle to compete with more experienced writers. Not all micro-entrepreneurs are able to open and set up their own accounts on these online working platforms. For example, Kohe, a tax and insurance consultant, was unable to pass the skills tests set by Upwork. “I tried joining Upwork but I failed the test.” Otieno, a shoe merchant who does online work on the side, doesn’t have an account on any online work platform and relies purely on outsourced work acquired through friends, or friends of friends. The availability of outsourced work gives those who are unable to open their own accounts, or struggle to win their own jobs, an opportunity to reap the rewards of the digital side hustle.

What risks are involved?

This process of reintermediation, in which successful online entrepreneurs outsource work to those who struggling to find their own work across these platforms, can lead to exploitation. Outsourcing also exaggerates the race to the bottom for wages and work conditions. Not only has the oversupply of labor created endless competition on platforms, but it has begun to filter offline and into the growing pool of outsourced micro-entrepreneurs. Estimations of oversupply of labor are therefore likely low, failing to account for the growing workforce who complete online work but don’t necessarily have their own online presence (even if they find this work through Facebook groups). Moreover, in addition to driving wages down, there are increased risks when a middleman, unregulated by the platform, is introduced into the workflow process. A number of the micro-entrepreneurs to whom we spoke highlighted the risk of accepting outsourced work through Facebook groups dedicated to online writing due to the risk of being conned into completing services without being paid. As Mary told us based on her experience in Kenya:

“There are many people who have not paid their (outsourced) writers.”

3. Off-platform support

The world of online work can be an overwhelming place. Online entrepreneurs, or those who desire to enter the world of online work, often seek support from off the platform. We found evidence of micro-entrepreneurs leveraging in-person support. While beneficial, this off platform support has its limitations. For Daniel, while a friend initially upskilled him on iWriter it took over a year to work out how to master the process:

“My friend explained it to me and I did a few articles. It’s a learning process.”

Kipchoge learned how to use StudyBay from his girlfriend. Initially she gave him some of the less complicated jobs After building up enough experience, he got his own account.

“Before I was in a position to actually complete a paper from a client, it took me like three months.”

Facebook groups dedicated to the world of online writing also provide support and guidance. Across these groups users share tips on how to set up accounts on the different online writing platforms. There are also opportunities to connect with trainers who teach people how to write and complete assignments.

4. Making the side hustle your full-time job

Through the process of bending rules, appropriating technologies, and hacking systems, some online entrepreneurs have been able to build relatively successful businesses through these online work platforms. As research by OII similarly found: “Some workers are able to thrive in platforms that reward entrepreneurialism by skilfully building their ranking scores, aligning their self-presentation with the needs of clients, and re-outsourcing tasks to be performed for even lower wages.”

Two of our interviewees, Kipchoge and Mary, “employ” staff to help manage their online academic and article writing businesses. Their digital side hustles have become their primary business. For example, Kipchoge earns 70% of his money through online writing. Mary does online freelance writing full time. She told us that many of her friends from university also do this type of work, mostly academic writing, as a full time job. “Yeah, some of them even come from the university to do it,” she told us. “They concentrate on it…They even have big offices, and they have writers in there…” Mary refers to her work as a business, not a side hustle.

But this work isn’t all smooth sailing. While gig work provides more jobs and the flexibility to either run it as a side hustle or main business, it comes at a cost. In addition to the challenges that come with an oversupply of labor, and the race to the bottom in terms of fees and work conditions, these platform exhibit an obvious imbalance of power between clients and freelancers, tilted toward the former. The idea that the client is always right rings loud and clear. As Mary explained, “Okay, so, academic writing specifically, you get some very unreasonable clients.” Kipchoge also pointed out this imbalance.

“For the platform administrators, clients are their customers so they don’t disappoint the customers. In most cases, they actually punish the writer.”

Read next: Tech and Touch ⇢