This takeaway piece is designed to help development institutions (donors, foundations, etc) think about where and how to intervene to shape the platform era to work best for micro-entrepreneurs.

Are you in the right place? If you’re more interested in understanding the implications of this research for platform design and business models, we recommend you have a look here. And if you’d rather read about how our project advances theory and research around “MSEs and ICTs”, look here. If you still think you’re in the right place, please read on! If you still think you’re in the right place, please read on!

Introduction

With businesses becoming increasingly digital, micro-entrepreneurs need platforms that work for them, include them and empower them, instead of exploiting them. On this page we offer three key takeaways for development institutions, highlighting areas where the right support could help micro-entrepreneurs thrive across platforms:

- Support micro-entrepreneurs offline to help ease digital transitions

- Encourage platforms to be drivers of transformational upskilling

- Develop strategies to protect the burgeoning online work community

We recognised that these three takeaways are small suggestions to help unlock a much bigger opportunity, that comes with its own big challenges. The success of the platform era in Africa is not guaranteed. As a recent report commissioned by the Mastercard Foundation points out, “there are many uncertainties shaping the trajectory of growth, and impact of these technology-enabled business models”. We hope our research will help highlight levers of action, recognising that these need to be addressed in tandem with much wider policy actions that will set the stage for promoting platformization, digital commerce and employment across Africa.

Takeaways

1. Support micro-entrepreneurs offline to help ease digital transitions

There are clearly winners and losers when it comes to the platformization of markets. Those who struggle tend to be individuals who are not yet fully digitally included in terms of device, data, and digital literacy. From our research, we identified a number of reasons why micro-entrepreneurs either struggle to get online, or are pushed offline. These range from monetary constraints when it comes to the cost of data, to digital literacy constraints in terms of a lack of understanding around how to build online credibility or navigate the complexity of e-commerce platforms.

We heard many examples of micro-entrepreneurs responding to these challenges by looking for offline support. For example, Daniel learnt how to access and navigate the iWriter online work platform through the help of a friend. And Robert, who sells mobile phone accessories through e-commerce platforms, benefits greatly from the offline support and training provided through Jumia. What’s important to note here is that despite digitization and platformization of markets, finding a balance between tech and touch is fundamental in helping micro-entrepreneurs transition to digital.

Examples of off-platform support tools

- Rural Connectivity Hubs: China’s Rural Taobao model is based on 30,000 service centers located in rural areas across China and designed to help rural customers, through support and training, shop online through their e-commerce platforms. Our partners at MercyCorps AgriFin Accelerate are starting to explore the concept of a similar rural hub model for their smallholder farmers. These hubs are designed to help smallholder farmers access transformative digital products and services in a physical offline location. The hubs would bring together different agricultural ecosystem actors, aggregating services while also providing offline training opportunities on how to utilize the digital products on offer.

- Offline Digital Literacy Training: Many low-income, first-time smartphone users lack the necessary digital skills needed to meaningful adopt and use the digital services on offer. While at present it appears that many of these skills are learnt through trial and error, some initiatives are trying to tackle these digital divides. A good example is GSMA’s “Mobile Internet Skills Training Toolkit”, which provides an introduction to using the mobile Internet—focusing on Google, WhatsApp, and YouTube—on an entry-level android smartphone. This toolkit is specifically designed for MNOs, NGOs, development organizations, and governments as a toolkit for offline training.

Proposed areas of support

- Develop a clearer understanding of the digital literacy needs of micro-entrepreneurs in the platform era and meaningful ways that providers, governments, and NGOs can facilitate necessary training.

- Encouraging platform players to find the right balance of tech and touch for both merchants and customers that transact across their platforms. Find inspiration here from our partners Accion Venture Labs.

2. Encourage platforms to be drivers of transformational upskilling

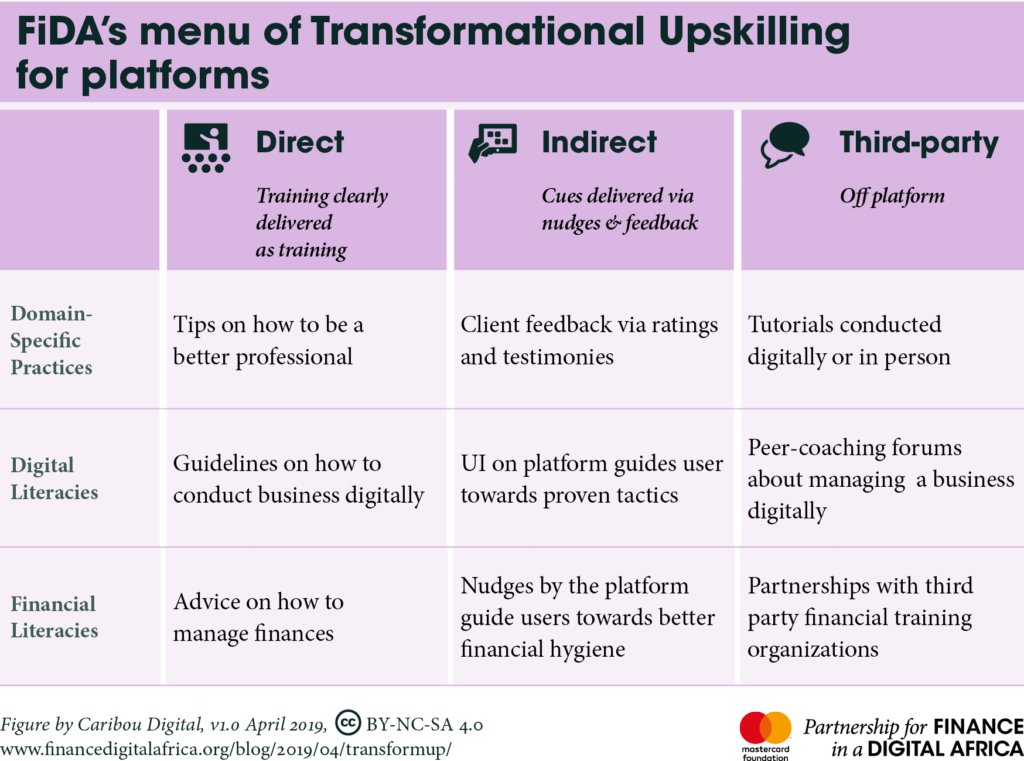

As noted above, the shift to platform use requires continuous support, as well as upskilling, and reskilling. We observed a number of channels, both on and off platforms, through which micro-entrepreneurs learn new skills and literacies. These ranged from comprehensive, platform-led training modules, to an informal helping hand from a family member or friend. We refer to the former – platforms that actively support and upskill micro-entrepreneurs -as “transformational platforms” providing “transformational upskilling”, and are eager to explore how this approach could positively impact both platforms and the micro-entrepreneurs that work across them.

Transformational Upskilling

Transformational upskilling allows platforms to prosper by facilitating learning, in win-win-win relationships with participants and labor markets. Platforms win by accelerating sales and increasing the quality of goods and services on offer. Producers win by learning new skills and improving their craft. Regions and countries win by increasing the human capital of their workforce.

Examples of transformational upskilling:

- Jumia:Jumia Kenya provides comprehensive online and offline training tutorials for their merchants. In addition the Jumia Vendor Hub provides information on how to use and maximize the backend Sellers Centre dashboard, as well as other basic tutorials on how merchants can grow their Jumia businesses. Jumia also supports a Facebook group and YouTube channel dedicated to providing access to e-commerce experts and other sellers.

- Upwork: Upwork, a popular online work platform among Kenyan micro-entrepreneurs, provides a number of channels for support and upskilling. Through their online community hub freelancers can ask questions, be linked to helpful tips and best practices, and access tutorial videos and webinars. They also provide skills tests and Upwork huddles—meetups hosted by top-rated freelancers.

Proposed areas of support

We believe, although this requires more research, that we should be encouraging platforms working in Africa to be more transformational, by providing opportunities for producers working across platforms to “learn new skills and improve their craft” It’s our hunch that a transformational upskilling model, either run by the platform or through a trusted intermediary with support and guidance from the platform, is a powerful way to drive broad-based financial and economic inclusion among micro-entrepreneurs in Africa.

Below is a rough taxonomy of how, according to our research, platforms can upskill their users. We encourage more investigation and research around this theme:

3. Develop strategies to protect the burgeoning online work community

Our research in Kenya reinforces other studies suggesting that many Kenyan micro-entrepreneurs have taken to online work platforms to support their side-hustles. This “online work” consisted mainly of freelance writing, product reviews, and surveys via online work platforms such as Upwork, iWriter, and Uvocorp. While we appreciate that our sample size is small, we believe the insights we gathered about micro-entrepreneurs presents an intriguing opportunity for further study and investigation.

In our platform practices section we discuss how users adapt technologies to fit their needs. We saw the appropriation and adaptation of platforms in full force when observing how micro-entrepreneurs behave across online work platforms. The impetus for this adaptation was due to both gatekeeping issues as well as issues of oversupply of labor. For example, to stand out from the crowd, micro-entrepreneurs risked incriminating themselves by buying pre-made and pre-rated accounts from third parties, using VPNs (virtual private networks) to change their “location”, and posting fake profile pictures in a bid to improve their credibility. We also observed work being outsourced from these platforms. This outsourcing, or reintermediation, results in an exaggerated race to the bottom for wages with already low fees being divided further.

We also observed work being outsourced from these platforms to both help account owners increase their reviews and ratings and provide work for those who struggled to survive amid the competition. This outsourcing, or reintermediation, results in an exaggerated race to the bottom for wages with already low fees being divided further. Not only are wages driven down, but risks are heightened with outsourced entrepreneurs, who have no direct relationship with the platforms through which they indirectly work, being exploited. One micro-entrepreneur told us that it was common not to pay outsourced writers. As online platforms grow, micro-entrepreneurs working across them need to be given a fair share of this economic progress.

Some good examples of initiatives focused on protecting and empowering the online work community

- Mark Graham and the Oxford Internet Institute have done some great analyses of online gig work in Africa and Asia, interviewing 125 micro-entrepreneurs in a bid to understand how regulators and platforms can help work towards a more fair world of online work. They argue that much of this activity passes under regulators’ radar. Their Fair Work project is aimed at identifying best and worst practices in emerging platform economies, and their recently launched Fair Work ratings highlights working conditions among a range of global and local platforms

- The International Labour Organisation have proposed a human-centered agenda for the future of work, which puts people at the center of economic and social policy. On the topic of online work, they argue for the establishment of a “Universal Labour Guarantee” whereby all workers would enjoy fundamental workers’ rights, an “adequate living wage” (ILO Constitution, 1919), maximum limits on working hours, and protection of safety and health at work.

Proposed areas of support

- Raising awareness among local African regulators

- Encouraging international standards for global online work platforms

- Helping local African online work platforms develop standards and best practices around protecting online micro-entrepreneurs

Concluding thoughts:

How this research links to the Mastercard Foundation’s ‘Young Africa Works strategy. The Mastercard Foundation are in the early stages of trying to understand broader technology and business trends, specifically around job creation for youth in Africa.

With a young and fast-growing population in Kenya, many Kenyan micro-entrepreneurs are, inevitably, young men and women looking for ways to generate a sustainable income. As platforms transform markets around the world this presents new opportunities, and challenges, for young micro-entrepreneurs to find work they see as dignified and fulfilling. We hope that by identifying both the positive and negative ways platforms are changing the future of work, we are contributing to the development of a platform landscape that provides youth in Kenya, and across the African continent, meaningful livelihood opportunities and more avenues for financial and economic inclusion.

Read next: Implications for Research ⇢