“The importance of meeting someone (in person)? According to us the importance is that you persuade that person and now he or she becomes a client.”

Rehema, Caterer

Summary of Findings

- Touch driving use of technology

- Tech and touch working in tandem

- Tech pushing micro-entrepreneurs back to touch due to:

- Lack of trust

- Lack of transaction facilitation

- In-person training

- Access constraints

Despite the increased digitization of both personal and business domains, there is no clear line between online and off. Rather, people engage in ‘tech and touch”. “Tech” refers to online, mediated interactions and “touch” to face-to-face communication. When looking at micro-entrepreneurs’ behavior across platforms, the reasons for the blurring of the online and offline worlds range from issues around trust to digital literacy constraints.

We see the blending of digital and human interactions across all technologies, from the use of e-commerce to simple mobile phone calls. Chepkirui, a hairdresser and one of the 27 micro-entrepreneurs we interviewed for our research, described why she uses both tech and touch with her clients:

“I just tell them to come so that we can speak face-to-face, because on phone it is so hard to convince someone.”

Findings from our research build on themes we’ve heard from our partners—and beyond—around the hybridity of tech and touch:

- Accion Venture Labs’ Tech and Touch Balance report shares lessons from successful startups that have managed to find innovative ways to balance digital tech with appropriate human interaction to better serve their customers.

- FIBR’s MSME and Superplatform research in Tanzania revealed how digitally augmented micro-entrepreneurs expressed interest in investing in offline services. All seven of the micro-entrepreneurs interviewed in the research were interested in the concept of a “pop up shop”, a temporary physical storefront enabling customers to come and try out products before they buy them online or in-person.

- BFA’s Catalyst Fund has also witnessed how tech and touch has positively impacted inclusive FinTech companies as they work to broaden and deepen financial inclusion. FinTechs that are not ready to fully digitize the customer journey have found that human interaction at the point of customer acquisition helps build trust and maintain customers.

- TechnoServe’s Smart Duka program in Nairobi, leverages both in-person trainings and WhatsApp support groups to upskill and upscale selected high-potential corner stores.

- Donner and Maunder highlight the blurring of online and offline strategies in their analysis of internet use by informal microenterprises in Kenya and South Africa. Using marketing as an example, Donner and Maunder discuss how “the market landscape in many places is becoming a melange of the old and new approaches: the offline and the online, the appropriated and the purpose built.”

This section, one of two detailing “additional observations”, shares insights from our interviews around the interplay between online and offline practices among micro-entrepreneurs in Kenya and the underlying incentives for them to dip in and out of platformatized markets as they go about their daily business.

The flow of “Tech and Touch” is multi-directional

From our in-depth user research, we saw the journey between tech and touch moving in multiple directions. Below we go through the three basic journeys we found:

1. Touch driving use of technology

With new technologies, human interaction is often needed to build trust, drive adoption, and encourage use. Even in the case of mobile money in Kenya, with 13 years of digital transactions under its belt, human interaction is still required at various points along the customer journey. In the case of micro-entrepreneurs and platforms, given that platforms are a relatively new technology for this user group, human touch is particularly important.

In the Upskilling section we discuss in detail how micro-entrepreneurs leverage in-person training and support to navigate and get the most out of the various platforms on offer. For example Faith, a fresh juice seller, despite leveraging various platforms (from Instagram to YouTube and WhatsApp) for upskilling purposes, found her most reliable source of information and advice was her mentor, Esther. Similarly Daniel, a micro-entrepreneur who does online freelance writing in the evening, was trained on his evening side-hustle by a friend. Asked how he knew how to use iWriter, a freelance writing platform, he told us:

“My friend explained it to me and I did a few articles. It’s a learning process.”

Micro-entrepreneurs also use human touch to build relationships with their customers before they move conversations online. Benard, a shoe merchant, uses his physical store to help market his shoes, attract customers, and build relationships. He then tends to move regular customers over to WhatsApp for on-going marketing and communication purposes.

“By the way, most of the customers I sell to (in the market), after that I just deal with them through WhatsApp.”

2. Tech and touch working in tandem

Tech and touch can also work together, complimenting each other. Rehema, a caterer, told us how in-person meetings with potential clients help build trust and solidify relationships while her Facebook page is a great way of promoting her products and services.

“You see some people will like to see what you do…It is hard for someone just to trust you once. You can’t just tell someone I know how to cook and maybe you don’t have evidence.”

Benard, a shoe merchant, communicates with his clients via WhatsApp, but goes offline to deliver the shoes in-person and receive payment. Similarly Faith—despite using a variety of platforms to communicate with clients, promote her goods, and upskill herself—delivers her juices in-person.

As discussed in the Search, Promotion, and Discovery section, many micro-entrepreneurs use a blend of social media platforms and offline tools in their buying and selling journey. Despite e-commerce sites (like Jumia and SkyGarden) providing an end-to-end service, we observed that self-contained, all-in-one messaging and coordination is the exception not the rule. Instead, most of the micro-entrepreneurs to whom we spoke use a patchwork of different social media platforms alongside phone calls and in-person meetings in the selling and buying cycle. Indeed, touch often comes into play for micro-entrepreneurs for the last mile delivery component.

3. Tech pushing micro-entrepreneurs back to touch

While the two above journeys, touch driving technology adoption and technology and touch working in tandem, are perhaps less surprising observations, our third journey focuses on technology pushing micro-entrepreneurs back into the offline world. The impetus for this is usually tied to a micro-entrepreneur’s issue with a platform, be it a breakdown in trust or inability to complete a sale (often due to the lack of an online payment mechanism).

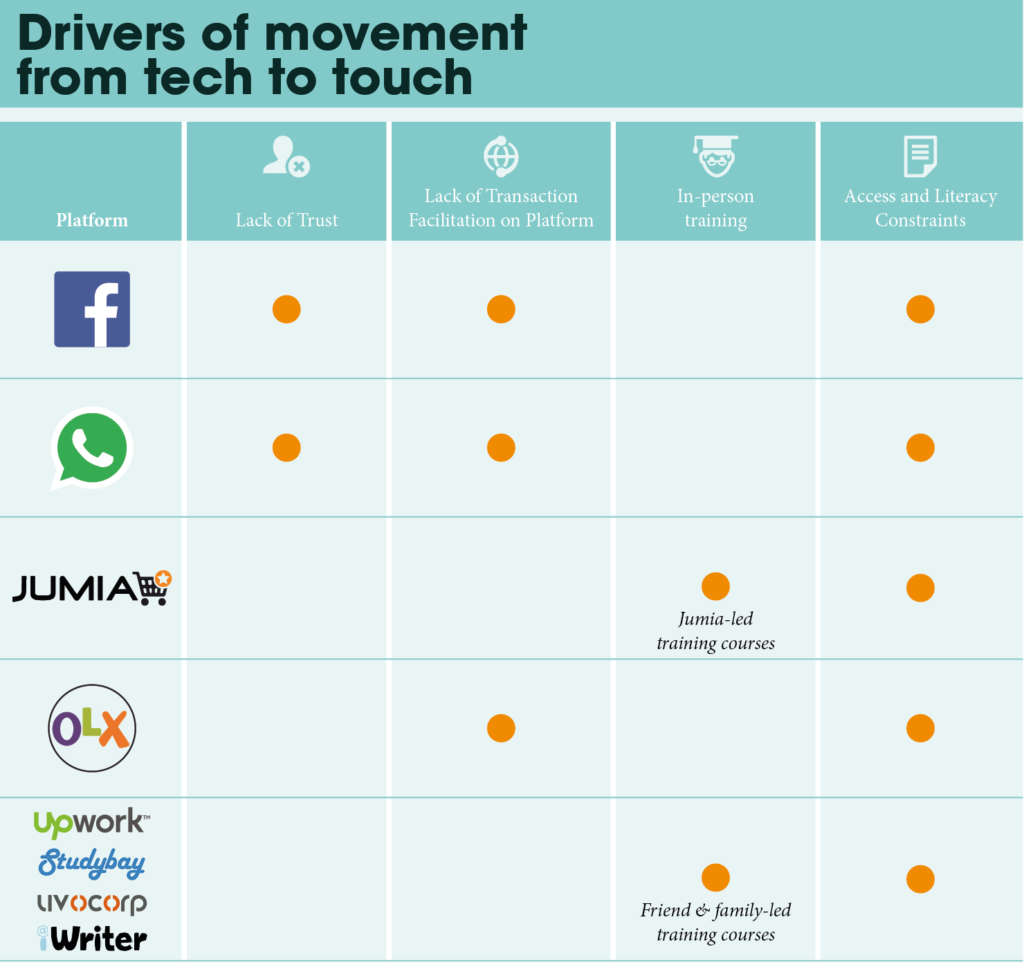

In the table below, we have mapped the drivers of this movement—from tech to touch —to the platforms most widely used by the 27 micro-entrepreneurs we interviewed in Kenya. For example, micro-entrepreneurs were mainly pushed off Facebook due to: lack of trust, lack of transaction facilitation, and access and literacy constraints.

Below we discuss each of these drivers in more detail.

Lack of trust

Trust is critical in all commercial transactions. When platforms work for micro-entrepreneurs, trust plays a central role.

Our conversations with micro-entrepreneurs revealed a lack of trust predominantly across social media platforms. Users of these large social media platforms contribute to the erosion of trust. Odeke, a micro-entrepreneur who uses a small team to distribute water for him in the traffic in Nairobi, explained that he had been scammed when looking for a job on Facebook:

“Jobs that are being posted there (on Facebook) are cooked, most of them. To get a genuine one is difficult. There are contacts there. When you call that person, they will tell you send money. So, it’s a game.”

Privacy concerns are also raised around Facebook. As Makena, a tailor, told us:

“You know Facebook has a lot of things and if you want to protect yourself, your privacy, you don’t just go on Facebook.”

Further, while the network effects of social media allow micro-entrepreneurs to increase their exposure exponentially, there is insufficient personal interaction to build trust-based sales. This is especially important for small businesses that rely on personal cachet rather than brand and reputation. Large platforms, such as Facebook, enable micro-entrepreneurs to widen their customer reach, but the larger their audience grows the less intimate it becomes. As Zawadi, a baker, told us:

“When it comes to Facebook, the challenge is not everyone knows you, you are just Facebook friends.”

As a result, when micro-entrepreneurs find a potential customer on Facebook, the relationship is often moved to WhatsApp. Micro-entrepreneurs appear to trust WhatsApp more than Facebook; accordingly WhatsApp plays a larger role in facilitating interactions and closing sales. The higher level of trust on WhatsApp may derive from the user experience and interface of WhatsApp as well as its closer connection to SMS messages. The fact that it is linked to a person’s phone number, a more tangible form of ID than a Facebook profile page, may also be a contributing factor. Otieno, a shoe merchant, told us why he views WhatsApp as more trustworthy than other social media platforms:

“The fact that you know the people rather than Facebook or Twitter where you don’t even who you are talking to…”

However, as observed in FIBR’s MSME and Superplatform research a number of our respondents commented on the overwhelming number of messages they receive through WhatsApp. Kioko, a small trader of flash disks, complained:

“I don’t like WhatsApp groups…you wake up in the morning and you find like 200 messages.”

Kipchoge had a similar attitude towards the platform, choosing to post on his WhatsApp status rather than through WhatsApp groups. In order to stand out among the sea of WhatsApp messages, Nduku, a micro-entrepreneur who runs a thrift store, calls clients before sending a WhatsApp message:

“I will talk to you first so that you expect it. I don’t just go posting, because you may see something from me and you don’t know what it means.”

Ultimately, when micro-entrepreneurs find a potential customer on a social media platform, a phone call or in-person meeting is seen as the most powerful and reliable way to close a lead. We’re not saying that no social media platform supports trust, rather trust grows when micro-entrepreneurs and their customers move from Facebook to WhatsApp and, ultimately, in-person communication (see “Tech and Touch Journey” image below).

For example, despite using Facebook and WhatsApp, Nduku who owns a small thrift store, viewed face-to-face interactions as her most powerful sales tool. A number of our micro-entrepreneurs also leverage their physical shop location to build ultimate trust with customers. Kerubo, a micro-entrepreneur who sells beaded jewellery, shared how she builds trust with customers:

“I just tell them come to my shop at Ngara and see for yourself if you don’t believe.”

Lack of transaction facilitation

The fact that micro-entrepreneurs cannot transact financially across certain platforms (namely social media), and therefore close sales, also forces them offline. And this isn’t unique to the platforms that micro-entrepreneurs have appropriated to fit their business needs, such as social media. Some e-commerce sites also take a hands-off approach when it comes to transaction facilitation. Unlike Jumia, which handles all transactions and interactions between buyers and sellers (even cash-on-delivery payments), OLX does not provide any mechanisms for payment. To transact and close a sale, buyers and sellers that have connected across the OLX platform must move their conversations offline and transact in-person. While there are inclusion benefits of enabling cash on delivery payments, it is “expensive, inefficient, and time-consuming for both merchants and buyers.”

In-person training

While various platforms provide opportunities for online upskilling (see more details in our Upskilling section), in-person support still plays an important role. We observed in-person training either purposefully being provided by a platform, or organically provided by family and friends to fill a skills gap. For the latter, friends, family, and acquaintances were called upon to help fulfil a variety of literacy and livelihood training needs. For example:

- Kipchoge was trained on how to use StudyBay, an online freelance writing platform, by his girlfriend.

- While Faith uses YouTube to watch upskilling videos and chats with a business coach via Instagram, her most valuable source of information is from a friend: “Yeah, because it’s face-to-face and I can tell her this is what I want and this is what I’d like to do, and she would tell me no, do this and that.”

- And Chepkirui relies on in-person training for her hairdressing business, highlighting that not all skills are conducive to online training: “It is hard for me to follow instructions from a video.”

Access constraints

Access barriers also contribute to the tech and touch approach. A number of microenterprises we spoke with connected their fragmented use of social media to the cost of data bundles. Zawadi, a baker, explained why she sometimes chooses to send an SMS over WhatsApp:

“If it’s WhatsApp, if someone doesn’t have data or maybe WiFi, they won’t see it on time.”

Similarly, when we asked Kioko, a micro-entrepreneur who sells flash disks through various on and offline channels, how Facebook could better help his business, he replied: “Stop charging. I can post anywhere, any time.” This metered mindset, in which people dip in and out of Internet access due to pricing constraints, is an important access concern and illustrates why a micro-entrepreneur might wish to transition a potential customer onto a platform that requires less data, or to phone calls or face-to-face communication. WhatsApp is also cheaper than Facebook, which could explain the transition from Facebook to WhatsApp or, as in the case of Benard, bypassing of Facebook completely:

“And my business, most of them, I do through WhatsApp…You see for the first thing WhatsApp is fast and WhatsApp is cheap.”

We also noted access constraints on online work platforms. A number of micro-entrepreneurs to whom we spoke had opened accounts on online work platforms but struggled to access jobs due to the massive oversupply of labor on these platforms. This pushed micro-entrepreneurs off the platforms, to either look for people who were selling pre-made, highly rated accounts (see more on this in the Digital Side Hustle section) or to look for outsourced work. Mary, a micro-entrepreneur we interviewed who employs four people to support her online writing, explained to us how she trained her staff off the platform:

“I realized working on my own, I don’t make much and I can actually pay someone to do it for me at a lower price. I got some people that I trained, now I just get to delegate them together on those jobs.”

It appears that various gatekeeping issues bounce some micro-entrepreneurs straight back into the offline world.