This takeaway piece is designed to help researchers build on this project in their own inquiries, advancing our emerging understanding about how micro-entrepreneurs have changed to thrive in the platform era.

Are you in the right place? If you’re more interested in understanding the implications of this research for design and business models, we recommend you have a look here. And if you’d rather read about the implications for policy and development interventions, look here. If you think you’re in the right place, please read on!

Takeaways

In this takeaway section we extrapolate from our 27 in-depth conversations with micro-entrepreneurs to highlight implications for future research in key topics that we think this work exemplifies, and areas that demand further attention.

Changing conversations—from phones and ICT to platforms

This study contributes to a line of research, going back at least 20 years, focused on microenterprises’ use of ICTs. Yet neither the existing work on phones/mobile phones nor the work on ICTs and the Internet in general is sufficiently calibrated to the realities that microenterprises across sub-Saharan Africa face today. This study illustrates how Microentrepreneurs’ markets are being platformitized in two basic ways:

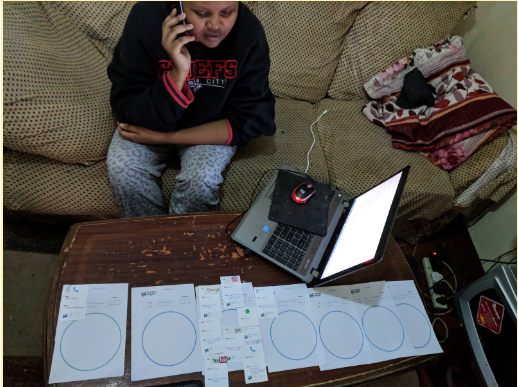

- Individual micro-entrepreneurs use social media platforms for informal and real-time coordination with suppliers and customers. WhatsApp and Facebook are the dominant players in this space, and to be clear, we are not talking about specialized “WhatsApp for business”, targeted at allowing larger businesses to respond to customers, or Facebook for business. These are simply the consumer facing omnibus communication platforms that are the lingua franca of digital Kenya. Our research, echoing BFA’s work with Tanzanian MSEs, underscores the remarkable flexibility with which micro-entrepreneurs have adapted these channels for their own purposes. The social media platforms are like toll-free numbers, customer relationship managers, billboards and direct mail, presales advertising, and after sales support all rolled into one.

- These markets are also being platformitized by the entrance of transaction platforms: specific websites designed to host multi-sided markets between buyers and sellers. OLX and Jumia were most active in Kenya. These sites have scrambled the traditional means of finding, transacting, and supporting customers. They increase exposure of MSEs to customers, but they also increase competition, and our work only scratches the surface of what this does to the bottom-lines and profitability of small enterprises. Strikingly little evidence is available to assess whether transaction platforms work well for small-scale producers—those who wish to sell via the platform. Instead, the platform literature has focused mostly on consumer welfare (lower costs, more choice) and the attractiveness of the platform model for platform operators themselves. We hope this work underscores, for the development/inclusion research community, the importance of focusing on the profitability and sustainability of being a small-scale producer or a self-employed gig worker on transaction platforms like OLX and Jumia.

The importance of asking “how”, not just “whether”

In our work, we are excited about how the FiDA platform lens, dividing platform functions into aggregation and discovery; transaction support; credibility; and ancillary data, enables us to detail whether and specifically how platforms are altering the landscape and prospects for small enterprises. We think this approach has merit for future studies, and we suggest that researchers zero in on specific models of change—specific ways in which the platforms they study, be they Facebook and WhatsApp, or specialized transaction platforms like OLX, are actually transforming the markets they enter. It’s also important that we get to granularity. Specific affordances matched with specific functions on specific platforms is where the rubber meets the road or, in this case, where the material meets the digital.

The need for specificity and replication

Ours was a relatively small scale study that engaged with a small set of microenterprises in and around Nairobi. A close read of our findings should quickly underscore the need for (1) replication beyond Nairobi, (2) specificity, into various market segments and types of microenterprise, and (3) complementarity of methods. Our interviews were largely qualitative, but there’s a need to drill down into documenting changes to livelihoods and quantifying any changes in the profitability and sustainability of these businesses. Our study also suffers from survivorship bias: we have only spoken to “live” microenterprises, and are unable to ascertain whether some micro-entrepreneurs are being driven from their markets thanks to platformization..

The need to avoid detaching studies of digitized, platformized markets from the real world

Our two blurring sections, on tech and touch and the digital side hustle illustrate the material component of digital pursuits. On the one hand, tech and touch shows that the realities of doing business in resource-constrained contexts may require more face-to-face time, more trust-building, more hand-holding, more creative ways of bridging the last mile in goods and and services. But what of those workers who bridge the digital and the material? What about those who require a combination of offline and online behaviors to earn a living? These dynamics are best unpacked with the type of ethnographic or qualitative work we were able to do in this study, and are worthy of future replication and exploration. As for the side hustles, digital or not, they challenge what we mean by a “job” or “a livelihood”. These digital side hustles, such as online essay writing or virtual assistant work, blur the lines between being an entrepreneur and being a contract worker, between being self-employed and being a franchisee, between being responsible for one’s own fate and captive to someone else’s algorithm. The work underway at the Fair Work Foundation and other research institutions is developing a body of evidence around digitized platform work in the global South. Our work contributes a key new finding regarding individuals who keep a foot in both worlds, one in a job or a tangible/material micro-business and the other, at night or in slack time, moonlighting in the digital space. Our discussions of what it means to use the Internet to pursue digital livelihoods, either as a primary or secondary means of income, can benefit from this attention to moonlighting in side hustles.

The need to put this research in dialogue with other efforts

There is a range of emerging research around platforms, from highly critical media-studies approaches to pragmatic development and business model inquiries. Admittedly, our work resonates with the latter approaches. One ongoing focus of work in this area can be found among the researchers engaged with DIODE, the Development Implications of Digital Economies Strategic Research Network, convened by the University of Manchester from 2017 to 2019. We found interactions with network members invaluable in formulating some of our ideas about how to study platforms and platformization, and we hope this work serves as a belated but still helpful contribution to the overall slate of DIODE outputs. Another helpful exchange has been with our co-travelers in the Mastercard Foundation community of practice, specifically BFA’s FiBR project, which has been looking at platforms used by micro-entrepreneurs in Tanzania, and Mercy Corps’s research into agricultural platforms in Africa. As a triad, these research efforts are highly complementary and shed light on changing practices, and changing market conditions, in eastern Africa and beyond.

The need to explore paths forward, perhaps particularly, of transformational upskilling

Finally, our work surfaced a few broad topics that could be avenues for further research. These include continuing challenges in maintaining and policing credibility; in creating trustworthy environments for transactions to occur, both on and off platforms; and in setting the conditions that promote local production and retention of value even in platformitized markets.

We are particularly excited about the prospects for platforms to build upon what they’ve already started, becoming digital spaces in which participants acquire a variety of skills and digital literacies required to thrive in the platform era. We call this “transformational upskilling” and will spend much of 2019 looking at this topic in a more comprehensive way. In the meantime some initial thoughts are available in the policy summary section.